The post Cfp – Situating Women’s Liberation; Historicizing a Movement Symposium appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The University of Portsmouth: Friday 4 July 2014

The women’s liberation movement (WLM) erupted into late 1960s Western society as a powerful force for social change, challenging rigidly defined and oppressive sex role stereotypes, promoting a set of formal demands for women’s equality and introducing terms such as ‘sexism’ and ‘male chauvinist’ into everyday language. There is little doubt that the women’s liberation movement had a profound impact, yet popular images of the original ‘women’s libbers’ portray second wave feminists as men hating, bra burning, dungaree clad harridans. There is currently renewed interest in feminism, and an upsurge of feminist activity. This has been accompanied by a desire amongst feminist historians to develop the historiography of the WLM. The aim of this one day conference is to historicize the women’s liberation movement within western society between c1968-1990.

Papers are invited in any area of women’s liberation c1968-90 in Britain, Continental Europe and North America. We are particularly interested in the following themes:

- ‘The personal is political’: consciousness raising, personal narratives, oral testimony – remembering the WLM;

- Sexuality and contraception, including lesbian, bisexual and transgender feminists, sexual violence and ‘reclaim the night’;

- Struggles at work: women’s strikes, equal pay, against sex role stereo typing – equal opportunities;

- The WLM and media: campaigns against sexist advertising;

- feminist publications;

- Black feminism;

- Women from ethnic minorities/ women of colour in the WLM;

- Cultural dimensions of the WLM: feminist art, theatre, writing;

- Transnational dimensions

This conference is aimed primarily at historians but will also be of interest to scholars in other disciplines, notably Literature, Cultural Studies, Sociology and Media Studies.

Please send abstracts up to 300 words to Sue Bruley ([email protected]) by 4th April 2014.

Website and Booking: http://www.port.ac.uk/centre-for-european-and-international-studies-research/events/situating-womens-liberation/

Local Information: http://www.visitportsmouth.co.uk/

The post Cfp – Situating Women’s Liberation; Historicizing a Movement Symposium appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

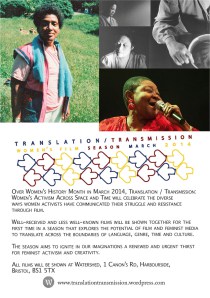

]]>The post Translation/ Transmission: Women’s Activism Across Space and Time Film Season, March 2014 appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>Translation/ Transmission brings together well-received and less well-known films that will be shown together for the first time in a season that explores the potential of film and feminist media to translate across the boundaries of language, genre, time and culture.

Translation/ Transmission features activist documentaries and women filmmakers from the Women’s Liberation Movement in Britain, Jamaica, Palestine, Germany, Vietnam, USA, Iran and France/ Cameroon, highlighting the diversity of different feminisms across geographical locations and historical moments.

Screenings will be enriched by discussion from activists, academics and artists; audiences will be invited to participate in discussions about the role played by feminist artists and filmmakers in rendering visible forgotten histories and marginalised experiences.

We are excited to be sponsoring the screening of Rapunzel, Let Down Your Hair and In Our Own Time which is taking place on Sunday 16 March at 1pm.

Check out the full programme.

The post Translation/ Transmission: Women’s Activism Across Space and Time Film Season, March 2014 appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Calling all Spare Rib contributors – from the British Library appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>Few titles sum up an era and a movement like Spare Rib. The magazine ran from 1972-1993 and for many women was the debating chamber of feminism in the UK.

The British Library has recently embarked on a pilot project to assess the feasibility of digitising the complete run of Spare Rib magazine. Although the entire run of the magazine has always been available to readers at the British Library and other libraries, digitising the copies and making them freely available online would transform access for researchers and the wider public.

As Spare Rib is still in copyright, in order for this project to go ahead it is crucial for the British Library that all Spare Rib contributors (including illustrators and photographers) grant permission for their material to be digitised and made available online for non-commercial use. The contributors and Spare Rib collective members we have spoken to date have been very positive but we still need to contact a great number of former contributors to ask their permission to digitise their content.

The British Library is undertaking a feasibility study between now and the end of December 2013 to see whether this will be possible. Without sufficient permissions to digitise the project will not go ahead.

If you were a contributor to Spare Rib then we want to hear from you! Please get in touch for more information by contacting [email protected]. If you could specify the approximate date you were a contributor and the name by which you were known that would be very helpful.

The post Calling all Spare Rib contributors – from the British Library appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Sheba Press & worries about link rot appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

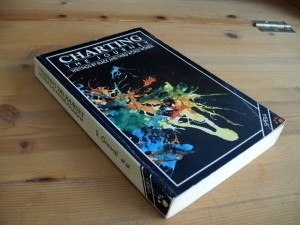

]]>So when conducting research about Sheba Feminist Press, who published the important Black British feminist text Charting the Journey in 1988 and many others, it was a relief to find some information about them.

What was slightly disconcerting was the nature of the web page, which appeared graphically old and was hosted by a US university site. It wasn’t being actively maintained and was the kind of link, you suspect, that would soon disappear.

In short, this is the rationale for reproducing the text below in its entirety from that web page in case it breaks, or vanishes.

For further information, the Women’s Library in London was donated records from Sheba Press (1980-1994) in 1995, but it remains uncatalogued and unaccessible to researchers.

Now there’s a funding bid that needs to happen!

ABOUT SHEBA FEMINIST PRESS

Sheba Feminist Press was established in 1980 — one of a handful of small independent publishers born of the UK women’s movement during the 70s and early 80s. The new feminist presses turned their backs on the high-modernist clique then firmly in control of the British book scene, and looked instead at what that world literally couldn’t see: the writing of women who hadn’t been to Oxford or Cambridge, and who weren’t necessarily white or heterosexual or middle-class, and who didn’t speak with the polished vowels of Bloomsbury. The new writers weren’t seduced by the pastoral English idyll of haywains and cottages and

servile, cap-doffing peasantry. They wrote instead about what it was like to live as an ordinary, non-privileged woman in post-imperial Britain in the second half of the twentieth century. The ordinary, non-privileged women who constituted a large part of the book-buying public found their own lives reflected in

these books, and responded with what can only be called devotion. The phenomenal success of women’s publishing was probably the single biggest factor in the dissemination of feminist ideas to

women in the UK.

Today, mainstream UK publishing has been persuaded of the marketability of women writers. Many large publishers have their “women’s studies” lists, and women novelists (some of them) get

reviewed on the literary pages, just like men. But old predilections die hard — particularly, in Britain, the predilections associated with intellectual and social snobbery: if more women writers are published now than in 1965, it remains true that the majority are white, heterosexual, and middle-class.

Sheba has a mission to challenge this persistent bias. We give priority to the work of women writers who continue to be marginalized. That means more than simply being ready to publish writing by women of colour, or lesbians, or working-class women; it means recognising the multiplicity of voices within these

communities — a multiplicity which is frequently overlooked by a world quick to categorize and dismiss. Sheba has built its reputation around its commitment to diversity, to difference, and to open and critical debate. One of our earliest titles was Feminist Fables — a retelling of myths, from a lesbian-feminist

viewpoint, by an Indian woman, Suniti Namjoshi. Published in 1981, when lesbian-feminists were universally assumed to be white, and Indian women universally assumed to be heterosexual, Feminist Fables called into question this cosy compartmentalization; it can be seen in retrospect as a harbinger of the coming

struggles over difference and diversity, which by the end of the decade had put paid to the myth of a unitary feminist identity.

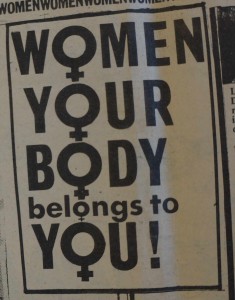

This commitment to openness and to diversity has made Sheba a key player in the ongoing feminist debates around sexuality. In the Seventies and the early Eighties, many women had a new and pleasurable sense of ownership over their bodies and their sexuality; and this was reflected in the books being published.

For Ourselves (Anja Meulenbelt, 1981) was characteristic: written by a woman, for women to read, it rejected the marriage-guidance approach which had previously dominated the field (“Doctor, my

wife is frigid. Can you help me?”) and acknowledged women’s sexuality as a private source of pleasure and power available to all women. Joanni Blank’s The Playbook for Kids About Sex (first published in the US by Down There Press) adopted a similarly positive attitude; children were encouraged to explore their bodies and to experiment with masturbation, fantasy, and sexual play. These and other Sheba titles contributed to the growing acceptance of women as autonomous sexual agents, rather than eternal objects, and helped to undermine the cultural prescription of what Adrienne Rich described as “compulsory heterosexuality”.

As the old prescriptions crumbled, however, new ones sprang up to replace them. The ideological association of sexuality with patriarchal power, expressed through pornography and rape, made sex seem synonymous with oppression. For women, desire was taboo all over again. In 1988, Sheba challenged this new puritanism by bringing out the UK edition of Joan Nestle’s A Restricted Country (first published in the US by Firebrand). The publication of this collection of essays and stories about lesbian sexuality acted as a catalyst on the simmering dissensions over lesbian sado-masochism, butch-femme relationships, and perverse sexuality, and gave the UK proponents of sexual autonomy an important cultural reference point.

The following year, Sheba built on the success of A Restricted Country, by bringing out Serious Pleasure, a collection of lesbian erotica . Although the controversy over pornography and censorship continues, it is clear from the popularity of Serious Pleasure and its successor, More Serious Pleasure that there is a strong and growing demand from many UK lesbians for well-written, explicit, woman-centred erotic material. (N.B. Serious Pleasure and More Serious Pleasure are published in the US by Cleis Press.)

Today, Sheba continues to prioritize the work of women of colour and lesbians. A number of prominent Black U.S. writers have been published in the UK by Sheba, among them bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and Jewelle Gomez. Sheba is now turning its attention to the exciting possibilities opened up by new technology, particularly multimedia and computer-mediated communications. We welcome the

new ease with which we can communicate with other women in countries all over the world; Sheba’s dedication to openness, fluidity, and the absence of boundaries finds a natural home on

the Internet.

Whatever the medium, the message remains the same: feminism, diversity, debate. If you would like to know more about Sheba, please write to us at [email protected]. We’d like to hear from you, and we promise to answer all messages. Sheba titles are available in the U.S. from Inland Book Co., and in Australia from Bulldog Books.

Sheba Feminist Press is a not-for-profit workers’ co-operative.

The post Sheba Press & worries about link rot appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Sistershow materials catalogued and searchable appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>

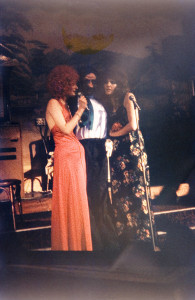

Pat VT West & Jackie Thrupp sit together under a giant hat that was made by Jackie for the first Sistershow performance in March 1973

In the meantime, enjoy these photos that we digitised as part of the project:

The figure dressed in red satin is Alison Rook, who donated a large archive for the exhibition, and was instrumental in getting the project off the ground.

Part of Helen Taylor and Brenda Jacques tape slide project that was used to raise awareness between women/ feminist groups about the activities and ideas behind women’s liberation

One of the few photographic documents of the Sistershow performances. This is the first show, that took place at Bower Ashton. Note the degradation of the image.

We still have catalogues from the exhibition available and you can get one for a small donation.

The post Sistershow materials catalogued and searchable appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Ellen’s Papers available on the Special Collections Catalogue appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>Ellen Malos’ archives are now searchable on the Special Collections catalogue at the University of Bristol.

They carry the classificatory mark of ‘Ellen Malos Papers, DM2123/8/112-128′ should you wish to find them.

Thanks to Sarah Cuthill, the project archivist, for her fantastic work getting all the papers organised to such a high standard!

The post Ellen’s Papers available on the Special Collections Catalogue appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Final Stop for Ellen’s Archives appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>Sarah stands in front of her handy work

Don’t forget, Ellen’s archives are available to consult so do get in touch if you want to see them. As always, you will need to plan your trip in advance to ensure the items you want can be retrieved from store.

The post Final Stop for Ellen’s Archives appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Final event for Ellen Malos’ Archives – documentation appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>We welcomed Cherry Ann Knott from the Heritage Lottery Fund, project archivist Sarah Cuthill presented the contents of Ellen’s archive, and Ellen provided a response.

The evening also launched our booklet What Can History Do? which is available for a donation through this website.

After the formal presentations, attendees had the opportunity to browse material from Ellen’s archive, as well as have good chat.

Thanks to everyone who came and participated in the wider project. We are working on some new ideas for funding bids, but will of course keep this blog updated with regular information about relevant events in Bristol and beyond.

Ellen’s archive is catalogued and available to view in the Feminist Archive South, so don’t forget you can pay us a visit if you are curious about its contents.

In the meantime, enjoy the photos!

The post Final event for Ellen Malos’ Archives – documentation appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Final Event for Ellen Malos’ Archives – 24 September 2013 appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>Project archivist Sarah Cuthill will introduce the contents of Ellen’s collection, followed by a response from Ellen Malos.

Ellen Malos was a key figure in the Bristol Women’s Liberation Movement. The first Women’s Centre opened in the basement of her house in 1973, and her work supporting vulnerable women has been recognised through an Honoury Doctorate at Bristol University (2006), and in the naming of the Next Link Women’s Safe House, ‘Ellen Malos House’ (12 June 2007). As activist and later, academic, Ellen was involved in advancing gender equality locally, nationally and transnationally.

Her archive comprises rare historical material, including documents that have shaped some of the most significant legal and policy transformations within British history relating to gender equality.

The presentation of Ellen’s archives will be followed by a report from Project coordinator Dr Deborah Withers who will discuss the outcomes of our workshop series.

The final event is also the launch the Feminist Archive South’s pamphlet What Can History Do?

The booklet, comprised of contributions from project volunteers, includes resources about

public history and the study of women’s history.

The final event is free to attend but places are limited so please confirm your attendance by

emailing us.

Refreshments will be provided.

Event address: MShed, Princes Wharf, Wapping Rd, Bristol BS1 4RN

MShed is a wheelchair accessible venue. Please contact us beforehand if you have other access

requirements.

The post Final Event for Ellen Malos’ Archives – 24 September 2013 appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>The post Reflections on the History of Bristol Women’s Aid workshop – 20 July 2013 appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>We’ve held a range of workshops and events over the past few months, including the history of feminist print media, film showings, archiving contemporary feminist activism, and singing with Frankie Armstrong.

For the last workshop we explored the history of Bristol Women’s Aid with Ellen Malos and Jackie Barron, unfortunately Nicola Harwin was unwell so she couldn’t join us – get better soon Nicola.

Here is some personal impressions of the workshop written by me (that’s debi, by way…)

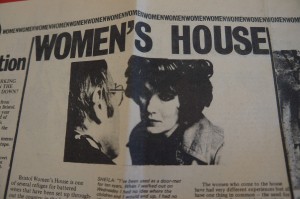

The early history of women’s aid in Bristol has been fairly well recounted on this blog – a single bed that happened to be in the Women Centre in 1973 was the seed from which Women’s Aid in Bristol grew. The centre often received calls from the police and the Samaritans to see if they could help women and children who were experiencing domestic violence, and it soon became clear that there was a real need for services to help vulnerable women in Bristol. Women and their children would take refuge in the centre for a few nights, but as the centre was a busy place they could not stay there all the time. In 1973 there was literally no support, and no understanding of the abuse women suffered, and it was commonly stated by authorities that women should just ‘go home’ to their violent partners.

As the calls to the women’s centre became more frequent, WLM activists began searching for a property where women could live safely. This became known as the ‘Women’s House Project.’ Recounting the early histories of women’s aid demonstrated how ‘women’s safe houses’ acted as spaces of mutual aid and co-operation, embodying many of the political ideals of the women’s movement as the first point on the document illustrates: ‘the house will be run on a day to day basis by the women in residence.’

The workshop revealed how WLM activists invented language to describe and analyse violence against women, including the very term we use today – ‘violence against women.’ Some of this language, such as ‘battered women’ now seems out-dated, and we reflected in the workshop on how terminology has changed as more became known about the field.

It might be worthwhile here to just pause a minute and consider: can you imagine living in a culture where there was no language to describe certain kinds of violence? As one contributor, who had been very involved in the development of women’s services in Bath commented, the analyses emerging from the WLM ‘prised open the private domain’ as an arena where women and children can experience physical and emotional violence.

A major part of the development of women’s aid and related services was research and policy reform. As Ellen was keen to state, women in the movement had no previous knowledge of law or social policy so they had to pick things up as they went along. This meant learning how the complex machinery of the state worked, negotiating dense bureaucracy and exercising immense powers of diplomacy. As Ellen jokingly reflected, she developed the skill to sit in meetings with sexist men, resist the urge to strangle them and maintain working relationships that helped them make incremental gains in attaining vital services for women.

I asked Ellen if she felt there was any tension between working so directly to reform patriarchal law and the aims of the wider movement that attempted to revolutionise the whole of society. As a socialist, Ellen personally felt there was no contradiction in pursuing such a course of action, but she did suggest there were people in the movement who were critical of these strategies. Ellen emphasised however that the women’s aid movement did not operate solely to change the law. It also aimed to change cultural perceptions and behaviour so that we can live in a world where violence against women is understood to be completely unacceptable. This is clearly an area where activism is vibrant in contemporary feminism, but there is still a very very long way to go before this aim is realised.

A revealing conversation from the afternoon focused on how the austerity measures implemented by the coalition government risk creating a situation where women’s financial independence will be curtailed, which could potentially mean women stay in relationships with violent partners. The introduction of a single payment of Universal Credit in October 2013 decrees that benefit payments can only be paid to one person per household, and does not stipulate the gender of the person money should be paid to.

Feminists have long emphasised the importance of women’s financial independence through benefit payments. Eleanor Rathbone argued for a system of family allowances paid directly to mothers as early as 1918. When threats to family allowance were tabled in the 1970s, women in the WLM mobilized to ensure that payments were still paid to the mother. The change to how benefit payments are structured in the UK may mean that payments go the man, therefore eroding what for some women is crucial access to financial autonomy.

Such changes in welfare policies demonstrate that the struggle for equality and cultural transformation at the heart of feminist politics is a continuous one. Advances can be made but they can also be retracted, particularly in an age of austerity where women’s freedoms are surplus to financial requirements. The workshop also demonstrated to me that understanding these struggles in a wider historical context is crucial, so that we can better understand how feminist incisions can be made in political and cultural life.

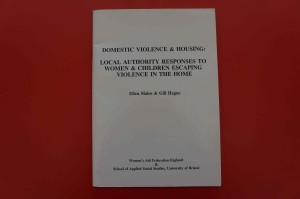

This was one of the first pieces of research to explore how local authorities were implementing laws to protect women escaping violence in the home

I hope that the plans to write the history of Bristol Women’s Aid is realised quickly. Contemporary activists would benefit from knowing how to make policy interventions and transform the law. It is clear that the current government is unpicking just about every progressive piece of legislation made in the 20th century. Sharing such knowledge and skills across feminist generations is vital for understanding the varied strategies of committed resistance women have collectively practiced throughout history. As I said earlier, the fight for equality and cultural transformation is a continuous one, and recording and sharing what we have done is an integral part of sustaining political action.

The post Reflections on the History of Bristol Women’s Aid workshop – 20 July 2013 appeared first on Feminist Archive South.

]]>